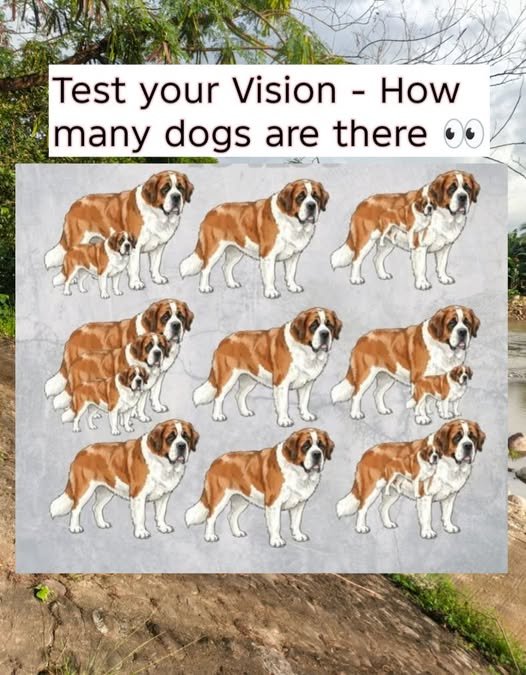

At first glance, this image feels like an easy count: a neat group of fluffy St. Bernards lined up, calm and obvious, almost begging you to say “nine” and move on. That’s exactly why the puzzle works so well. Your brain naturally locks onto the boldest shapes first, and once it feels like it has a complete picture, it stops searching. The trick isn’t that the extra dogs are invisible—it’s that they’re quiet, blended into the design in a way that rewards a slower, more deliberate look.

Most people land on 9 because those dogs are the most clearly drawn and placed front-and-center. The hidden animals are different: they’re partially blocked, tucked along edges, or disguised as background curves. A shadow that looks like scenery becomes a back, a stray line becomes an ear, and a soft patch of shading turns into a muzzle once you trace it carefully. The puzzle takes advantage of how the eye favors strong outlines and ignores subtle transitions, especially when we’re confident we’ve already “solved” it.

To find the full total—15 dogs—use a simple method: scan in sections rather than staring at the whole image. Start at one corner and work across slowly, looking specifically for single features (ear tips, paw shapes, tails, or partial faces) instead of complete dogs. Then ask one question repeatedly: Could this curve belong to another dog? Many of the hidden St. Bernards share outlines with neighboring dogs, meaning one contour can serve two figures, which is why your first pass misses them.

The fun part is what happens once you spot one of the “extra six”: your brain learns the artist’s hiding style, and suddenly more dogs begin to pop out. That’s the real value of puzzles like this—they train patience and perception, and they remind you how often “obvious” answers are only obvious because we stop looking. Try it again, compare counts with someone else, and see if you can uncover all 15—because the picture holds more than it admits on a quick glance.