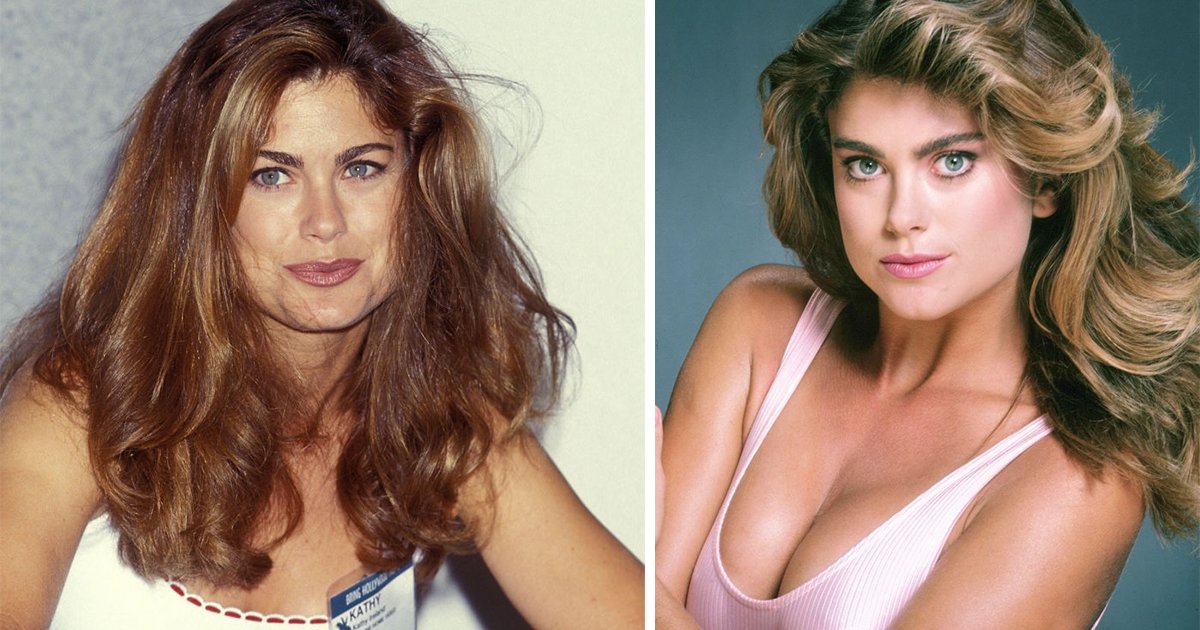

In 1989 a girl from Santa Barbara stood on a beach in Hawaii, red hair whipping across her face, holding a bright beach towel like a victory flag. That Sports Illustrated cover sold more copies than any before it, yet the woman staring back at the lens was already bored with being looked at. Kathy Ireland had learned early that beauty could open doors, but she refused to let it be the only room she ever entered. So while cameras clicked, her mind was busy balancing spreadsheets she had sketched on the back of her planner: socks, licensing fees, profit margins—clues to a life that would not depend on bikini weather.

She had started at sixteen, discovered in a high-school corridor by a scout who saw legs first and ambition second. The modeling world wanted her silence; she gave it a black eye—literally—when a photographer shoved her toward topless shots and she decked him. The moment became legend among models who were told to shut up and pose. Kathy’s rebellion was quieter off-set: she carried business books in her tote, asked questions about manufacturing margins, and kept a journal of product ideas between castings. While others counted calories, she counted potential customers—millions of middle-income moms who wanted cute, affordable socks and didn’t care who posed in the ad.

The sock line launched in 1993, the same year critics said her fame would fade. One hundred million pairs later, Kmart begged for a full clothing collection. Warren Buffett, charmed by her questions and homework, advised her next leap into home furnishings. She followed his counsel the way she once obeyed stylists—except now the fittings were for dining chairs, not swimsuits. By 2003 her company, Kathy Ireland Worldwide, was grossing billions, and the girl once valued for cheekbones was signing paychecks for hundreds of designers, engineers, and freight drivers. The power suit replaced the swimsuit, and she wore it like armor stitched with invoices.

She never claims magic. She quotes her father, a labor-relations executive who taught her to place the newspaper on the porch, not the driveway: over-deliver, under-promise, give 110 percent. She quotes Elizabeth Taylor, who defended her when Hollywood snickered at her acting attempts and later mentored her through the maze of licensing contracts. Taylor told her glamour fades but grace is renewable, advice Kathy stored like gold in the vault of her memory. The mentorship saved her during the years she juggled toddlers and trade shows, breastfeeding in hotel suites minutes before keynote speeches.

Today, at 62, she hikes the Santa Barbara hills she grew up roaming, ocean on one side, red-tiled roofs on the other. Surfing, biking, and long walks keep her lithe, but she refuses to chase the mirror. “I wouldn’t go back a year,” she says, because every wrinkle carries the memory of a deal closed, a hospital funded, a child taught to read. Her diet has no forbidden foods, only balance learned from decades on planes where dinner was whatever the cabin handed out; she simply asks the earth for more fruit, more color, more crunch. Brussels sprouts, once childhood enemies, are now roasted into crispy candy she shares with grandchildren who think Grandma’s office smells like cinnamon and possibility.

She still models, but only on her own terms: a photo to promote literacy, a campaign for foster care, a portrait beside the new line of sofas that bear her name. The red hair is touched with silver, the blue eyes softened by laugh lines, and the smile—the same one that sold magazines—now sells the idea that a woman can be the product and the CEO, the face and the factory, the cover girl and the cover story. Kathy Ireland outgrew the lens by stepping behind it, and in doing so she gave every girl watching permission to believe beauty is the beginning, never the boundary.